The Italian Mafia and the Move Upstream

Operation ‘Tiburón Galloway’ began as a local investigation by prosecutors in the Italian region of Calabria in 2001, but quickly snowballed into a multinational, multiagency investigation. Over five years, prosecutors uncovered a vast cocaine trafficking and money laundering conspiracy spanning both Italy and Colombia – and even the retirement plans of one of Colombia’s most notorious warlords.

The investigation into the alliance between Salvatore Mancuso, a commander of Colombia’s paramilitary army, the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia – AUC), and the ‘Ndrangheta mafia revealed just how far the Italians had come in the cocaine trade – all the way to the source.

According to reports in the Italian media, the evidence showed the Italians were buying cocaine from Mancuso in Colombia at $3,000 a kilo then organizing its shipment through Colombian ports and via Venezuela to Europe, where it would fetch prices up to 15 times higher on the wholesale market.

Mancuso, in turn, went into the business with the Italians in Colombia, even opening an Italian restaurant in the Caribbean city of Barranquilla frequented by mobsters and local elites alike. And as the paramilitaries negotiated their demobilization with the Colombian government, he sent one of his personal fixers to Italy to scout property deals, according to an investigation by El Espectador. Communications intercepts between ‘Ndrangheta members hinted at why:

“[Mancuso] is at the end of the peace process, and they will surely give him a couple of years in prison, then after he is coming to Italy,” Mancuso’s chief mafia business partner told his son.

Mancuso did not get his retirement in Italy – at least not yet. He was instead extradited to the United States, where he served a 12-year prison sentence on drug trafficking charges.

Since then, the European cocaine trade has changed and evolved. But networks organized along the same lines as the Mancuso mafia ring are becoming more common as ever more European traffickers move upstream in search of cheap cocaine and coordinate its dispatch Europe directly.

Nonetheless, it was the Italians, with their particular brand of organization, entrepreneurship and criminal efficiency, who pioneered the move upstream. And it is still the Italians who have the most far-reaching and sophisticated upstream operations.

Cocaine Brokers and the Criminal Diaspora

Italian involvement in the cocaine trade even pre-dates the rise of the Colombian cartels, with records of mafia members arrested in Brazil for cocaine trafficking as far back as 1972. But at first, cocaine was a minor part of a broad criminal portfolio that included everything from international heroin trafficking to local waste disposal rackets.

When Colombia’s Medellín and Cali cartels began to ramp up cocaine trafficking into Europe in the 1980s, the Italians were among the main wholesale buyers, moving and selling the product that Galician smugglers brought in for the Colombians.

But the Italians’ experience in the heroin business offered them a major competitive advantage over other European mafias getting into the cocaine trade.

“They exported heroin from Europe into the United States so they had a lot of experience and they had established distribution and importation chains,” said Mike Vigil, a former chief of international operations for the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

The more forward-thinking mafiosi understood that this experience and criminal infrastructure could be used to traffic the cocaine themselves.

“They came to Colombia so they could be closer to the supply and coordinate shipments to their standards,” said Vigil.

By the early 1990s, Italian cocaine brokers were stationing themselves in the country, where they worked quietly reshaping the European cocaine trade. The most infamous was the baby-faced trafficker Roberto Pannunzi, the man dubbed the “Copernicus of Cocaine” by Italian crime writer Roberto Saviano.

Pannunzi’s first realization was that the heroin he had trafficked for years was worth much more to Latin American traffickers than the cocaine they shipped to Europe. As Saviano describes in his book ZeroZeroZero, he began a drug exchange of 1 kilo of heroin for 25 kilos of cocaine. His second realization was that there was far, far more money to be made from cocaine upstream.

By the early 1990s, Pannunzi had leveraged his cartel contacts in Colombia and his mafia contacts in Italy to set himself up as an upstream middleman, establishing himself as one of the original cocaine brokers. He worked for himself, brokering deals between the Medellín Cartel and both the Cosa Nostra and ‘Ndrangheta mafias, but beholden to none of them.

The cartel era was winding down, with the killing of Pablo Escobar in 1994 and the capture of the Cali Cartel bosses in 1995 ushering in a new generation of traffickers and organizations. Pannunzi was captured in Medellín less than two months after Escobar’s death. The police officials arresting him turned down his offer of a million dollars to let him go, according to media reports at the time. Nevertheless, he was released five years later after prosecutors ran out of time to bring their case against him.

By that time, Colombia’s criminal monoliths had splintered into federations of smaller trafficking networks. For the Italian mafia, that represented new opportunities, and their footprint upstream began to grow.

The mafia that proved the most adept at moving in the new cocaine trade was not one of Italy’s infamous and storied mafias like the Cosa Nostra, but the ‘Ndrangheta, a relatively minor federation of family crime clans from the impoverished region of Calabria.

The ‘Ndrangheta plotted a chart upstream by turning a weakness into a strength. Poverty and lack of opportunity drove a mass migration of Calabrians, and among their numbers were ‘Ndrina – the mafia clans that make up the ‘Ndrangheta network.

“Migrants from Calabria created communities around the world and they strengthened the connections with the Calabrian region – this was the first base of their network,” said Alessia Cerantola, an investigative journalist at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and co-founder of the Investigative Reporting Project Italy (IRPI).

These migrant crime clans not only dedicated themselves to crime but also setting up legal businesses as fronts for illegal activity and to launder money. Among them were export companies, which the Italians used to ship cocaine to Europe in cargo and containers – what would become the main method of shipping cocaine to Europe.

This upstream presence allowed the ‘Ndrangheta to cut out the independent brokers and control more of the supply chain directly.

“They have their people in the key positions in the supply chain,” said Cerantola. “This is not only in Italy but also on an international level thanks to the people they located in key strategic roles around the world.”

Italian migration was key to the alliance between the ‘Ndrangheta and Salvatore Mancuso, who was the son of an Italian migrant from the southwestern region of Campania, and came from the city of Monteria in Colombia’s Caribbean, home to a significant Italian diaspora.

Mancuso, though, was far from the only ‘Ndrangheta supplier, as their upstream brokers set to work making other connections, not only with right-wing paramilitaries but also guerrilla insurgents.

By 2006, as the AUC was coming to the end of its demobilization process as part of a peace deal with the Colombian government, the ‘Ndrangheta was handling up to 80 percent of European cocaine imports, according to a report commissioned by Italy’s anti-Mafia commission.

The Italian Mafia and Cocaine Migration

In 2008, Salvatore Mancuso was extradited to the United States for continuing to traffic cocaine after his demobilization, along with 13 other paramilitary commanders. It was a watershed moment for the cocaine trade, as the old guard walked off the criminal stage and a new generation jostled to take their place in the Colombian underworld.

Since then, the European cocaine trade has opened up, both geographically and strategically. Now, there are more routes and more actors involved than ever before. But the Italian mafia remain at the forefront of this expansion.

Police and intelligence sources all around Latin America report their presence. In Brazil, today one of the main dispatch points to Europe, according to Europol, police sources described how they uncovered an alliance between the ‘Ndrangheta and Brazil’s most powerful criminal group, the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital – PCC) in 2017. In Costa Rica, intelligence sources say they are the most common European actor found trafficking in the country, while in Peru, police report that the Italians are among the main financers of cocaine shipments.

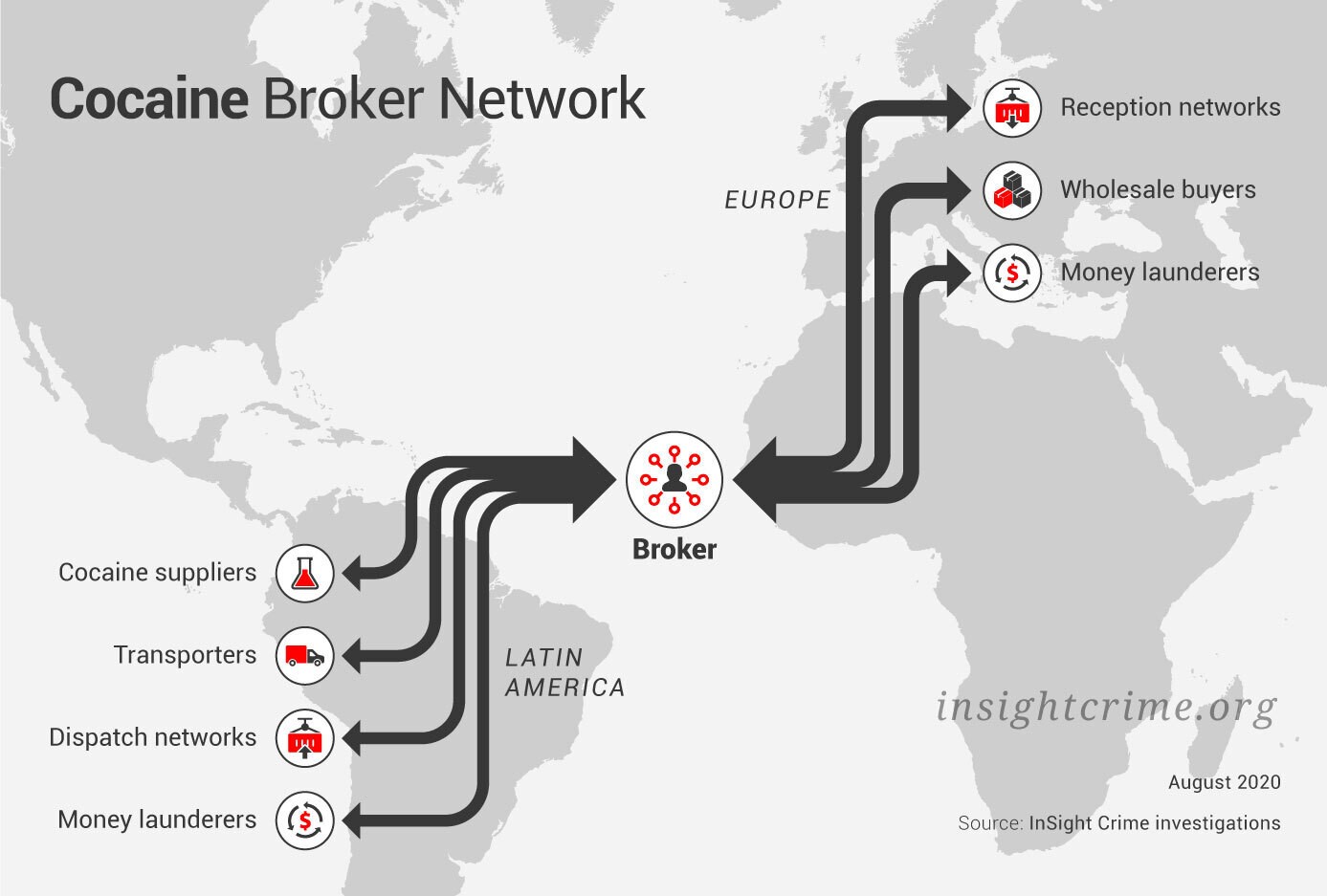

Brokers, many of them resident upstream, remain the lynchpin of their operations, with their connections to suppliers and dispatch networks.

“The ‘Ndrangheta have brokers in these countries, typically in Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, the Dominican Republic and Costa Rica, and these brokers try to organize the sales from these countries using legal businesses,” said Maurizio Catino, an expert on the Italian mafia and author of the book “Mafia Organizations.”

“In these countries, there are ‘Ndrangheta logistics cells for trafficking cocaine through the movement of goods for export to North America and Europe,” he added.

An IRPI and CORRECTIV investigation into one of these brokers, Nicola Assisi, offered a glimpse into how they work.

According to the investigation, Assisi established himself as one of the cocaine world’s leading brokers after he inherited the contact book of the legendary trafficker Pasquale Marando, who had worked alongside Roberto Pannunzi as one of the pioneers of Italian cocaine trafficking. When Marando was murdered by rivals in 2002, Assisi moved to take over the upstream networks he left behind.

Evidence collected by investigators shows how Assisi sources cocaine from suppliers in Peru, Paraguay and Brazil. He then contracts the PCC to move the cocaine to the port of Santos and dispatch it to Europe, where his ‘Ndrangheta clients are waiting.

Assisi, like Roberto Pannunzi before him, is an independent operator rather than a member of an ‘Ndrangheta clan. Most trafficking networks prefer it this way because it avoids the alerts that known mafia members would raise upstream, according to Esteban Chavarría, the head of the anti-narcotics unit of the prosecutors’ office in Costa Rica, where the Italian mafia currently has a major footprint.

“They do not directly form a part of the mafia in Italy, they have not been arrested and they have not been investigated, but they know the Costa Rican market and they come to form this link, a bridge between the mafia and Costa Rica,” Chavarría said.

The relationship between Assisi and the PCC is also typical of today’s Italian trafficking networks, where the brokers contract local criminal groups to handle the export. However, in some cases, the Italians have set up their own front businesses for sending cocaine shipments.

One of these cases ended with murder, when an Italian trafficker who set up a front fruit company in Costa Rica was gunned down in San José after a lost shipment. Chavarría believes it was not an isolated case.

“We are investigating more of these structures that have been set up by Europeans to carry out this type of trafficking,” he said.

Italian mafia operations have been uncovered in many other countries that have become – or are at risk of becoming – major cocaine export platforms supplying the European market, such as Ecuador, the Dominican Republic, Suriname, Guyana, Uruguay, Argentina, Bolivia, the Dutch Caribbean, and Chile. The ‘Ndrangheta alone operates in more than 30 countries around the world, according to European police.

However, these networks are far more than just cocaine trafficking cells. They are also master manipulators of illicit finance flows, which they channel through Latin America and the Caribbean. In some places, they have turned their money into power, by spreading corruption and penetrating vulnerable states.

One of the most audacious attempts to coopt upstream states came on the Caribbean island of Curaçao.

After gaining autonomy from the Netherlands in 2010, Curaçao elected Gerrit Schotte as its first prime minister. However, the country’s first independent government was compromised by Francesco Corallo, a casino owner in the region and, according to Italian prosecutors, an international drug trafficker who was an important member of the Sicilian mafia.

Investigations into Schotte revealed how Corrallo bribed the Curaçaoan politician to gain access to confidential government information and to secure the appointment of his relatives and allies in critical positions at the Central Bank, the Gaming Board, and within Schotte’s cabinet. In 2016, Schotte was convicted of forgery, official bribery, and money laundering.

Latin America and the Caribbean are also used as a refuge for Italians mafiosi on the run from the law, needing to lie low or looking to take semi-retirement by laundering money in the sunshine.

Just such a criminal retirement ring was broken up in the Dominican Republic earlier this year, when Interpol arrested eight Camorra fugitives, who had fled Italy after being convicted of crimes ranging from cocaine trafficking to embezzlement. The men – all but one over 50 – were living quiet lives allegedly laundering money through restaurants and tourist businesses.

The Italians are no longer the only European criminals setting up operations upstream. More and more groups – above all from the Balkans – have followed the path they forged upstream to maximize profits from the cocaine trade. Today, it is common to hear of Serbs buying cocaine at the source in Peru, or Albanians organizing shipments through the ports of Ecuador.

However, the Italians’ generations of experience moving both drugs and money, their global networks, and their proven capacity to innovate and adapt will ensure they remain among the most powerful and innovative criminal syndicates, posing serious security threats not only in Europe, but also upstream in Latin America.

*Investigation for this article was conducted by Maria Fernanda Ramírez, Douwe den Held and Owen Boed.